Men, Masculinity and Machines: Are men most likely to commit mass shootings?

Valentine’s Day. February 14, 2018. It was an ordinary Wednesday afternoon when the halls of Stoneman Douglas High School were forever altered by the haunting echoes of gunfire. Panic gripped the air as students and teachers, once focused on textbooks and lessons, now scrambled for cover. The once-familiar halls transformed into a surreal battleground where fear and confusion reigned.

This tragic event marked one of the deadliest school shootings in American history. As the nation grappled with the aftermath of the Parkland shooting, investigators sought to understand the complex factors that contributed to such devastating acts of violence. One alarming trend that emerged from analyses of school shootings is the disproportionate involvement of males in these incidents. Diving into the psychology and social reasons behind this pattern reveals a troubling narrative that intertwines mental health, societal expectations, and the need for a deeper exploration of the root causes of such atrocities. Why is it that Nikolas Cruz, along with hundreds of other men, decide to commit such a horrible and inhumane event?

Before I continue, I want to explain what a mass shooting is. A mass shooting is when one or more people purposefully hurt or kill others in a public place. This can happen at various locations where many people are present. The attackers choose victims and places either randomly or because they hold some meaning. The attack causes harm to multiple people, including both injuries and deaths. This event happens within one day, usually lasting only a few minutes. It’s important to note that the reason behind the shooting is not related to gang violence or planned militant or terrorist actions.

I’m sure the average person living in the world today, including you, has heard at least one more account of there being a mass shooting. In fact, since 2014 in the United States alone, almost 42 million people have lived within a mile of a mass shooting (Uzquiano). But for a second, let’s step outside the box. I mentioned in the beginning that men are most likely to commit mass shootings, but I also want to mention how men, in general, are also most likely to be violent. The truth is, men commit more violent crimes in general, three times as often as women do (United States Department of Justice).

From a young age, women are told to be cautious around unfamiliar men to stay safe. This warning, while aimed at protection, can unintentionally contribute to viewing men as potential threats.

Society often expects men to be strong and dominant, making it hard for them to express vulnerability or seek help. This pressure, along with other factors, may lead some, mostly men, to resort to violence as a way to assert power. The link between societal expectations, gender roles, and violent acts like school shootings emphasizes the importance of discussing mental health and challenging stereotypes to create a safer and more understanding society.

Now, every day when I wake up to get ready for school, these thoughts always linger in my head: “Will I be next?” Let’s be honest; we can all agree that most school shootings are caused by men. To name a few, there’s Virginia Tech, where a 23-year-old student named Seung-Hui Cho took the lives of thirty-two students and faculty members through two separate attacks on the campus before ultimately ending his own life. In the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, 20-year-old Adam Lanza perpetrated a heartbreaking act, killing twenty-seven people, including twenty first-grade children aged six and seven, along with six adults, which included his own mother.

During the Robb Elementary School shooting, 18-year-old Salvador Ramos entered a classroom, shooting both children and staff members present. He engaged in gunfire with law enforcement officers who had arrived on the scene an hour earlier but did not enter the classroom. In the University of Texas tower shooting, 25-year-old engineering student and former U.S. Marine Charles Whitman ascended the clock tower at the University of Texas-Austin. Whitman killed three people inside the tower and continued his rampage by firing from the observation deck, claiming the lives of twelve more people and injuring 31 others during a 96-minute shooting spree. The ordeal concluded when police shot and killed Whitman.

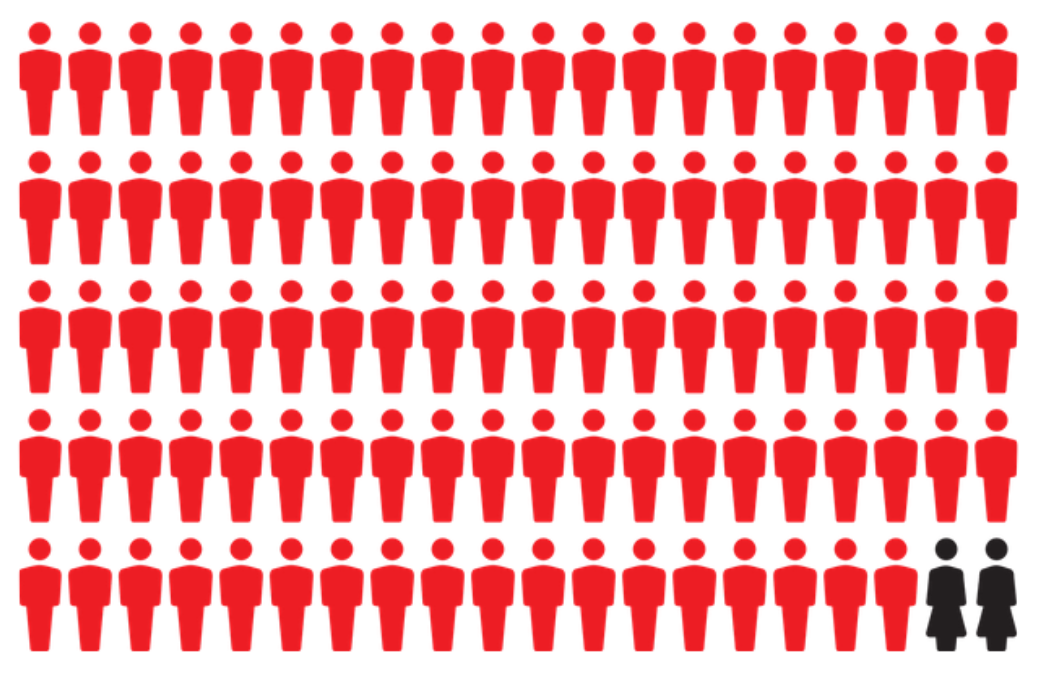

According to the SUNY Rockefeller Institute of Government, the number of mass shootings in the United States is 441 from 1966-2022 with 3,923 victims (both injured and killed). 95.7 % of the shooters were male. You can see that comparison on the graph . Ever since I started hearing about mass shootings and school shootings, I always wondered why it’s always men that do that? And honestly, in general, why is it that men are most likely to act violently in any situation? I’m sure we have all thought about it, but is there a deeper and more complex reasoning behind this question?

In “Speaking of Psychology: How to stop mass shootings, with Jillian Peterson, PhD,” special guest Peterson said something very interesting; he said, “So in our database, it’s 98% men. There’s four women in the database; two of them perpetrated the shooting with a man. So we see this common pathway, and of course, it’s a little different for each person, but this pathway seems to start with really significant early childhood trauma. Things like physical abuse, sexual abuse, suicide of a parent, domestic violence in the home. Over time, that individual becomes angry, becomes isolated, becomes hopeless, there’s a lot of self-loathing there. Many of them are suicidal and attempt suicide before doing a mass shooting.” Men, more so than women, often express their issues outwardly and may seek others to hold them responsible, potentially leading to feelings of anger and resorting to violence. Additionally, when women do resort to violence, firearms are typically not their preferred means of carrying out such actions.

Now, many people say, “Well, can we predict if a person is about to mass shoot?”. Many will argue yes, but I believe no. In “Why mental illness can’t predict mass shootings,” writer Nsikan Akpan states, “Approximately 96 percent of violent crimes— including shootings — would likely still occur even if every suspect with a mental health condition was stopped before they carried out an attack.” Think about this way; in America itself, approximately more than one in five U.S. adults have mental illness. That’s 57.8 million adults in America alone. To awe you even more, 1 in every 8 people in the world has mental illness, which is 970 million people living with a mental disorder or anxiety or depressive disorders, etc. How possible would it be to figure out, out of 970 million people who will shoot up a mall, school, or workplace next?

It simply wouldn’t be possible. Dr. Jonathan Metzl, a psychiatrist and director of the Center for Medicine, Health, and Society at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee said, “Most of the research shows that people with mental illness are actually less likely than the general population to go on to shoot somebody else or to commit mass violence.” Let’s say you have a magic wish to make one thing go away from this world. Whether it be world hunger, climate change, extreme poverty, or deforestation. Now you get to choose to get rid and cure all mental illness in the world. Should we successfully eliminate mental illness tomorrow, an amazing achievement, our issue with violence would decrease by approximately 4 percent, meaning the majority of the problem would persist.

While doing my research for this paper, I came across an interesting theory. According to NPR, researchers suggest that men, more than women, tend to blame others and externalize their problems, leading to potential anger and violence which I mentioned previously. When women resort to violence, guns are not typically their weapon of choice. In the context of mass shootings, where men significantly outnumber women as perpetrators, there’s a concerning trend. Male shooters often become role models for subsequent attackers, especially among young, white men. The Violence Project data implies that white men are disproportionately responsible for mass shootings compared to other groups. This phenomenon involves aspiring shooters identifying with and copying those who came before them. For instance, many school shooters study incidents like Columbine, while university shooters may look to the Virginia Tech shooting as a blueprint for their actions. This is also called “The replacement Theory.” Almost all school/mass shooters want to be remembered by name. They want to be remembered for how many people they got to kill and if their number is higher than the previous. It is truly a sick mindset.

To conclude, how exactly should the world deal with school/mass shootings? My answer to that is we need to work backward, figuring out the root of the problem. The problem with that is there are endless possibilities. The shooter might have a domestic abuse problem, might have been bullied in school, might have been rejected by a certain person(s), easy access to a gun. The most obvious concern I believe is the easy access to purchasing a gun. According to “Many mass shooters acquire guns legally” author Erin Doherty states, “From 1966 to 2019, 77% of mass shooters purchased at least some of the weapons used in the shootings legally.” More than 80% of the assailants responsible for K-12 shootings stole their guns from family members (National Institute of Justice).

I believe Congress should push to further ensure safer gun ownership, which involves better background checks for those buying firearms. We can do this by looking into someone’s history, mental health, and criminal record. This can better spot potential risks and keep guns away from the wrong people. Parents need to be extra careful with where they keep their guns, especially if there are kids around. Using more secure options like gun safes or lock boxes can help prevent accidental discoveries by curious children/teens. It’s also worth considering hidden storage that’s easy for the owner to access quickly but keeps the gun away from anyone who shouldn’t be messing with it. In the haunting aftermath of mass shootings, we can see a troubling pattern emerge – an insane number of male perpetrators. Masculinity, with its toxic expectations, plays a role in these tragic events. The solution lies in redefining masculinity, fostering environments that encourage emotional well-being, and dismantling the stigma around mental health.

Additionally, we need to address gun control and stricter rules to prevent people from having easy access to lethal weapons. If we all confront and educate each other on this issue, we can possibly help prevent the next mass shooting.